Ozempic for Sleep

Pharma and biotech do not take sleep seriously enough.

All neurological disorders are sleep disorders. Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, depression, autism, schizophrenia, Huntington’s, epilepsy, bipolar disorder, etc. are all intimately intertwined with sleep. Recent research even suggests it causes or precedes many.

Moreover, beyond GLP-1s, sleep is one of the only true population-scale opportunities. One-third of all humans complain about their sleep quality. And, virtually all humans would love better sleep if they could have it.

How much would they pay for it? People spend $100B a year on sleep enhancement products. And, none of them work. Öura is valued at $10B and all it does is tell you what you already know: that you sleep like crap when you booze heavily the night before. If people will pay hundreds of dollars for a crude measurement tool, undoubtedly they’d pay many multiples for something that actually works to improve their sleep.

How much would you pay for a pill that gives you deep, restorative sleep in 6 hours with no adverse effects? $100/mo? $1,000/mo? $2,000/m0?

I’d imagine almost no one in pharma would expect that people would pay over $1k:

How much would you pay for a pill where

— Mackenzie Morehead (@mackenziejem) December 11, 2025

You sleep 6 hours

Get deep, restorative sleep in + wake up feeling great

With no long-term side effects

The main thing that the GLP-1 phenomenon has taught us is that the way to create outsized value in pharma is going upstream of many diseases, early in disease progression, and in an indication for which the value proposition is blindingly obvious to consumers to enable DTC. How many fit indications that bill?

And yet, pharma and biotech have almost completely neglected sleep research, investing less than 0.5% of R&D budget.

That’s in part due to our relatively crude understanding of sleep, but also because the industry only thinks of disorders that are strictly related to sleep like obstructive sleep apnea, insomnia, and type 1 narcolepsy. While these indications still have unmet need and have previously delivered four blockbuster drugs plus several more doing $300M+ a year in sales, they’re now flooded with generics that cost 30 cents a pill from z-drugs to benzos to sodium oxybate to eventually DORAs. We’ve met researchers with exciting pre-clinical assets that couldn’t get pharma interested after KOLs warned they wouldn’t prescribe it.

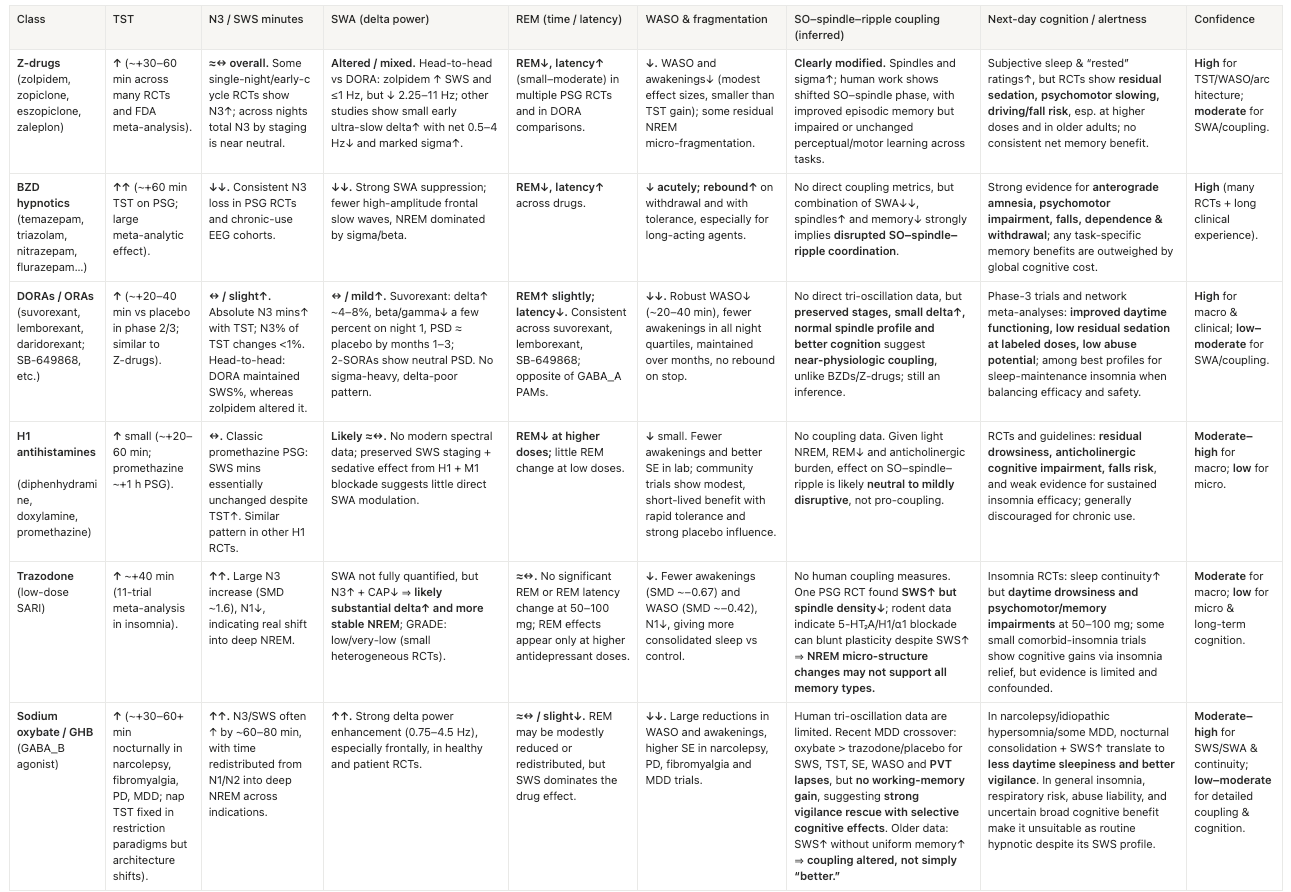

However, these generics very likely won’t work for the aforementioned population-scale indications. They indiscriminately engage receptors expressed commonly throughout the brain (e.g. GABA, histamine, orexin, adenosine) with at best coarse receptor-subtype tuning, effectively lobotomizing activity across the entire brain and creating unnatural sleep. See the Appendix for a breakdown of how existing drugs impact sleep.

Second, they target the specific neurons that are disrupted in narcolepsy and insomnia, each of which are distinct MoAs from one another and certainly from more common disorders.

While these previously targeted sleep disorders all have entirely distinct MoA, a bull case is that the more common forms of sleep disruption may share more MoAs in common. That could enable not only targeting of large indications like AD or depression but indication expansion from one to another and possibly to all of us that’d like to sleep better.

The Emerging Toolkit for Network-Level Understanding

Finding a path to these large indications requires modernizing the way sleep research is done. Historically, sleep research has focused on the few highly validated neurons associated with narcolepsy and insomnia, anesthesia-induced sleep in mice, and on ablating specific neurons in mice to see what happens downstream (which isn’t that relevant for the common sleep disorders where those neurons are intact).

Only recently has the field started to shift towards studying large-scale network interactions across the brain including in relatively healthy brains, other cell types beyond neurons like astrocytes, astrocyte-neuron interactions, and the glymphatic system.

Excitingly, we increasingly have the toolkit to do so, including:

- Chemogenetics and optogenetics

- Neural circuit tracing, largely in animals or complex organoids

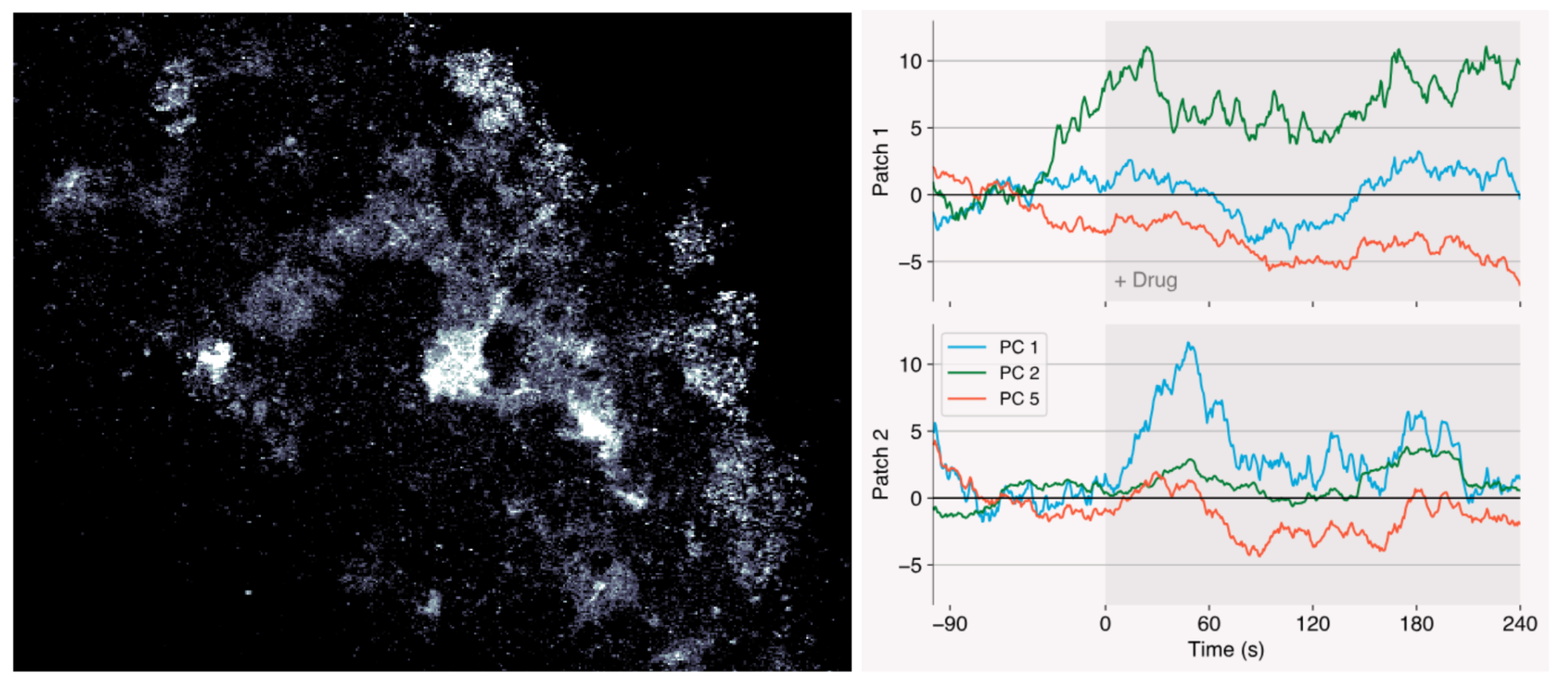

- Brainwide calcium imaging. Karl Deisseroth’s lab is pushing towards cellular resolution

- Simultaneous EEG-fMRI and EEG-PET-fMRI measurements to explore neuronal signaling, metabolic, and hemodynamic processes in humans

- A wireless device for continuous measurement of glymphatic function in humans

- Imaging methods to track vascular and fluid-flow dynamics across cell types in natural mouse sleep

- Single-cell transcriptomics and proteomics are only recently being applied at scale

- Tools to manipulate myelin dynamics

- Wearables to enable objective population-scale sleep tracking

- Tools to manipulate microglia including CSF1R inhibitor that take out microglia, applying optogenetics to microglia, large GWAS studies for non-neuronal cells

Of course, advances in ML pipelines have been essential to make sense of all this data.

While the field is still reasonably early in its methodological development, it’s worth thinking through how they could be applied to treat patients.

Aspects of Sleep to Target

A Good Night's Sleep In a Pill

Slow wave activity (SWA), a hallmark of the NREM phase, is considered the core driver of deep, restorative sleep. It’s not entirely clear if SWA alone is sufficient but it’s certainly necessary. Maximally boosting it with negligible off-target effects is our best shot at delivering a good night’s sleep in a pill.

Boosting Memory Consolidation

The mechanisms for sleep-based memory consolidation depend largely on the coordinated interplay between slow oscillations, thalamic-generated spindles (~10-16 Hz), and hippocampal sharp-wave ripples (~100–200 Hz). Clinical trials with existing drugs across diseases indicate that both the density of spindles and their timing in relation to SOs are important for memory.

Clearing Brain Gunk

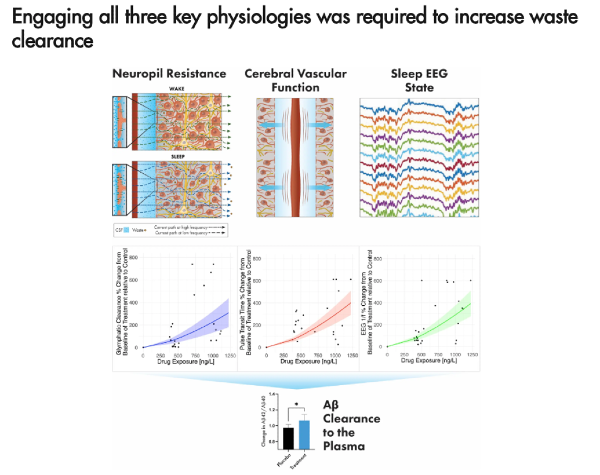

SWA also helps activate the glymphatic system. Though it appears reduced parenchymal resistance and increased cerebrovascular compliance may also be needed for effective clearance of gunk from the brain, including amyloid and tau.

Approaches to Targeting Them

- Over time, many neurons have been implicated in SWA. However, the circuits, their feedback loops, and the interbrain interactions remain incompletely mapped out. A high throughput, network-level but high resolution in vivo imaging or tracing technique could help flesh out our understanding of these dynamics in natural brains. Maybe what I’m describing is a platform for far more sleep but neurobiology broadly.

- Many presumed high leverage SWA nodes are neuronal types expressed commonly throughout the brain like GABAergic neurons. Brain wide flooding of these targets is exactly what leads to the indiscriminate activity suppression of current sleep drugs. Are there nodes with markers, pockets, or allosteric binding sites unique to the desired brain region to enable preferential small molecule binding? Are there other modalities that are far more selective, BBB penetrant, safe, and small molecule-like ease of administration (e.g. macrocyclic peptides, nasal administration of peptides, nanobodies)?

- Some particularly exciting targets include regulators of homeostatic sleep pressure as they’re intuitively upstream of the complete set of activations we’re after. When we’re sleep deprived, we sleep more deeply thereafter to catch up. What if we always did?

- Modifying existing drugs that substantially boost SWS like Trazadone to remove unwanted side effects

- Possibility for an AD / dementia treatment that combines a SWA stimulation device with a therapeutic that enhances spindle coupling to engage both the glymphatic system and memory consolidation

- Exploring glia targets, their network-level encodings, and their interaction with neurons

- A truly differentiated hardware device for non-invasive phase-locked SWA stimulation via acoustics, EEG, etc. That these technologies increase SWA is fairly well-validated at this point, though by how much and long-term effects are less clear. 5-10 companies have pursued this direction, several claiming signals similar to commercial polysomnograms and effective algorithms. So we’d want to see neural network-trained targeting and especially a meaningful advance on the hardware side to be more comfortable, user friendly, and precise targeting. Maybe a multifunctional eye mask or ear plugs?

Treating Sleep Like a First-Class Indication

Alzheimer’s

The dominant therapeutic approaches in AD target a single misfolded protein or reduce protein production. Even those that have successfully cleared such proteins haven’t alleviated the disease because they act just before disease symptoms become outwardly visible, which turns out to be far too late. Moreover, those strategies may simply be putting a Band-Aid on downstream pathology.

Revitalizing the brain’s natural restorative and waste clearance systems is an unsung hypothesis in an otherwise crowded space.

Circuits involved in SWS and the glymphatic system become disrupted 20 years before disease dementia onset and may be some of the first upstream causal.

However, consensus still doesn’t view sleep as a key risk factor. We’re here to highlight that there’s strong evidence it should be.

1) Genetics evidence & population‑scale studies

- While SO frequency largely remains intact, the amplitude is significantly deteriorated

- Sleep EEG features track cognition better than blood markers in a large study

- Sleep disruption (OSA, insomnia, abnormally high and low amounts of sleep) predicts cognitive decline and higher Aβ/tau burden. These conditions are also far more common in those with AD. With that said, these population-scale metastudies aren’t unanimous likely because what matters most is quality and quantity of SWS not TST.

- Those with genetic risk factors like APOE4 are even more likely to have sleep disruption

2) Human mechanistic experiments

- Neural slow waves are followed by hemodynamic oscillations, which in turn are coupled to CSF flow

- In a RCT, reduced glymphatic resistance predicted next morning amyloid and tau clearance more so than SWS in a multivariate model. Conversely, it also showed that increased SWS with increased glymphatic resistance had a negative effect on clearance.

- A large sample clearly implicates AQP4 in fluid clearance

- After 31 hours without sleep, hippocampal amyloid PET signal increased ~5%

- Overnight disruption of SWA without full awakening increases amyloid-β levels acutely, and poorer sleep quality over several days increases tau. TST didn’t explain it.

- Sleep deprivation increased unphosphorylated tau and altered specific phospho‑tau sites in CSF.

3) Mechanistic animal work

- Rescuing a circuit that generates SWA by stimulating GABAergic neurons or astrocytes in the anterior cortex slowed AD progression and restored memory impairment. Using Ambien boosted SO amplitude by 50% and transplanting stem cells with optogenetic boost fully restored it. Whereas, restoring hippocampal gamma waves had no effect.

- In tau models, chronic sleep disruption accelerates tau misfolding and spread, amplifies microgliosis, and causes enduring LC/amygdala neuron loss.

- In amyloid models—especially with APOE4—sleep deprivation increases plaques and neuroinflammation, disrupts AQP4‑mediated glymphatic flow.

- Sleep disruption accelerates pathology by degrading aquaporin-4 polarization and impairing microglial clustering—failures exacerbated by the APOE4 genotype.

4) Medical interventions

- So far, the clinical trials testing sleep drugs have been inconclusive in part due to their design. Most study patients that already have disease symptoms, are short-term and assess neither SWA nor glymphatic function, limiting their implications for evaluating this hypothesis. Most of these show some sleep benefits but negligible cognitive effects.

- One brief suvorexant treatment in cognitively normal adults lowered CSF Aβ38/40/42.

- Trials of phase-locked acoustic and transcranial direct current stimulation boost SWS in older and cognitively impaired adults. Greater enhancement loosely tracks better memory and more favorable plasma Aβ42/Aβ40. However, these trials have been small with relatively weak controls.

The most interesting results will come from currently enrolled trials for longer-term AD prevention, ideally with SWA and/or Aβ readouts.

While the connection between sleep and AD is somewhat clear, an effective drug would likely have to be used preventatively for many years, especially those not focused on glymphatic readouts. That yields difficult and expensive trial design in addition to unusually high safety requirements. So it's worth considering others.

Major depressive disorder

Large meta-analyses of longitudinal and prospective cohorts suggest insomnia and insomnia severity increases risk of later developing depression by 2x. CBT-I appears to benefit sleep and symptoms. OSA also increases depression risk by multiples. For those without insomnia or OSA, sleep disruption also seems associated with depression and better NREM may lower risk.

Mechanistically, one night of total and partial sleep deprivation leads to about a 60% amplification in amygdala reactivity to negative stimuli and reduced functional connectivity with prefrontal regulatory regions. It essentially creates a hyper‑reactive limbic system with weaker top‑down control. And in mice, chronic sleep disturbance produces depression‑like behaviour, reduced hippocampal neurogenesis, and BDNF changes.

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is characterized by dysfunction within the thalamortical-hippocampal circuit that generates and synchronized spindles. Weakened SDMC helps explain the patient’s quickened cognitive decline. Current therapies have not resolved this issue, with trials suggesting all three oscillations of SO, spindles, and ripples and their synchronization are necessary to improve memory. Though currently unclear if sleep is upstream or downstream of disease pathology, poor sleep and low sleep spindle activity are early indicators of schizophrenia, appearing before diagnosis or medication. These deficits, along with cognitive issues, have also been observed in unaffected family members.

Other Indications

Sleep disruption is also implicated in Parkinson’s[1,2,3,4,5], bipolar, PTSD, post-traumatic headache, Huntington’s [1], epilepsy[1,2], autism[1], ADHD[1], inflammation, cardio-metabolic axes, among other severe diseases.

Lastly, for more common diseases, quality sleep can decrease odds of getting the cold by 3x per a human challenge study, 2x antibody titers following vaccination, slow aging, etc.

Something for Everyone

While sleep’s implication in diseases is becoming clear, a main risk for this thesis is that we simply don’t understand the biological mechanisms nearly well enough and that the current methodological tools won’t get us there soon.

The field is only just now starting to transition from a coarse understanding to something more fine-grained and networked.

The uncertainty of making a drug in this space could be partially offset by the fact that there's few bio things the DoD would shell out more non-dilutive grants for than a drug that enables soldiers to sleep less. Grants are already written to the tunes of $10-100Ms for more contrived systems than a drug.

And, a hit would be more than worth it.

After making it to market through the indications above, a drug that boosts natural, deeply restorative sleep without side effects could expand to the general, relatively healthy continent-scale populations like GLPs.

If the drug also somehow enhances the coupling of the three oscillations and / or glymphatic flow, then it also could confer memory enhancement and AD protection.

A good night’s sleep in a pill is one of the few ideas with a shot at being the next trillion dollar molecule.

Appendix: Existing Sleep Drug’s Effects