The Fickleness of Scaling Laws

Or, the Foundations of Foundation Models

Nothing has defined tech in the last five years more than scaling laws. LLMs demonstrated consistent returns to scaling to dumbfounding sizes and cracked the positive feedback loop of scale to larger size to make a more useful product to raise and make more money to scale larger. After that, the hollow but universally repeated mantra of “bigger = better” was applied to every single domain conceivable.

While people still call them “laws” as if they apply everywhere all the time, very few teams in any other field beyond LLMs have convincingly demonstrated them at impactful scales.

Moreover, the number of people on earth that could thoughtfully articulate scaling laws beyond “bigger = better” could likely fit in one building.

What actually causes scaling laws in both theory and practice, what are their preconditions, when do they stop, why have they worked in some fields but not others, etc.? Some of those questions even remain largely unknown.

Before we dive in, a disclaimer that when we say scaling laws have rarely been robustly demonstrated, we're not denying that more data and compute will generally improve a model's fit to its training distribution or that plenty of papers in each field show performance gains to some degree.

We’re referring to scaling properties so robust that they maintain through more than a couple orders of magnitude (OOM), are independent of underlying technical assumptions, that produce models that can be used to answer novel scientific or commercially-relevant questions, and ideally that lead to generalization.

What are Scaling Laws, In Theory?

Shockingly little work has been done to systematically understand in theory or in general what causes scaling laws, determines their slope and robustness. Most existing papers frame it in terms of the dataset’s information density and diversity.

The initial work that made scaling laws famous framed the problem as function approximation: bigger networks carve up the underlying data more finely, so error falls predictably as model capacity grows.

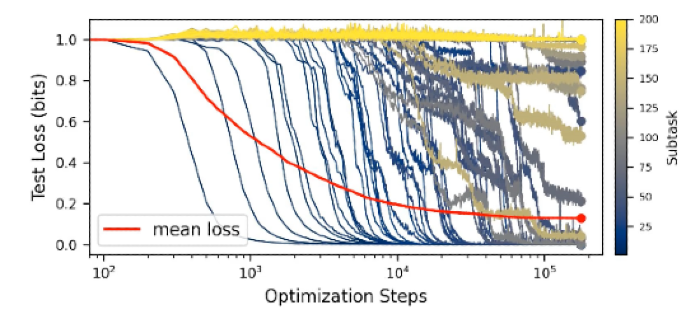

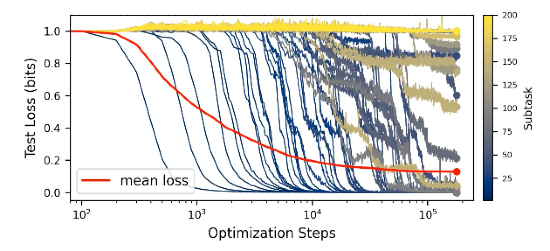

Recent work has tried to reconcile a tension at the heart of scaling research. Loss curves during training decline smoothly and predictably, yet performance on specific sub-tasks often snaps from failure to success in a near-binary phase transition as the model grows (aka grokking or emergence).

The quanta hypothesis offers one resolution. It proposes that networks learn discrete modules (each one a different algorithm or piece of knowledge) in order of how frequently they appear in the data. Because each module is tiny relative to the whole, many small, abrupt transitions average out into a curve that looks smooth from a distance.

Later papers have extended this framework further by suggesting that skills have hierarchical dependencies (a “skill tree”) rather than being independent and just ordered by relative frequency. Others seek to unify the discrete subtask perspective with the continuous function approximation view by modeling the data as having a percolation-like structure, where connectivity thresholds govern when new capabilities suddenly click into place.

Other work suggests that superposition yields more robust scaling, higher dimensional data scale more slowly, certain tasks (e.g. classification vs next-token prediction) have different scaling properties, and that general capabilities emerge abruptly at larger scales and cause the scaling exponent to temporarily steepen.

Either way, scaling laws eventually fade when the model exhausts the learnable information in the dataset and begins overfitting, the loss plateaus at a floor set by the dataset's inherent noise, or the data manifold becomes unwieldy.

Preconditions and Best Practices for Robust Scaling

Given the varied outcomes different fields and teams within those fields are experiencing, how should new teams think about what are the preconditions to be met before they even think about scaling up?

If you don’t have all or most of these firmly in place, you may be wasting compute by scaling up.

Being Exceptionally Thoughtful Around Exact Goals and What is Necessary

The more we’ve observed teams inside and outside our portfolio and researched this topic, the more our biases have shifted towards a key differentiator being thinking very clearly, deeply and precisely beforehand about both the technical problem and ultimate product’s commercial use.

Such teams treat scaling like a very well thought through experiment where they know exactly what hypothesis they’re testing, make sure they have controlled everything possible to test it, do series of small-scale experiments before gaining the confidence that a larger one is worth it, etc.

What tasks do you care about? A lot of people just want bigger models that do a lot of things, but that’s wasteful without precision about what specific tasks matter.

Dataset

- Is your pre-training dataset sufficiently diverse? Pre-training gives the most diverse background of the subject possible. It of course must include plenty of data that mirrors the downstream tasks but is often okay to have both good and bad examples. While we haven’t found highly sophisticated methods to assess information theoretic density, some simple tests can be done to proxy for diversity like how much information do you lose when you cluster datasets down as well as domain-specific diversity tests.

- If modeling the rare long-tail occurrences in the data is what matters, then how can teams operationalize that? Compound portfolio company Wayve has pioneered world modeling to generate the rare freak accidents that determine safety while Recursion used a small model to filter their dataset down by 5x by upsampling microscopy examples where the cell responded to a perturbation which is generally rare.

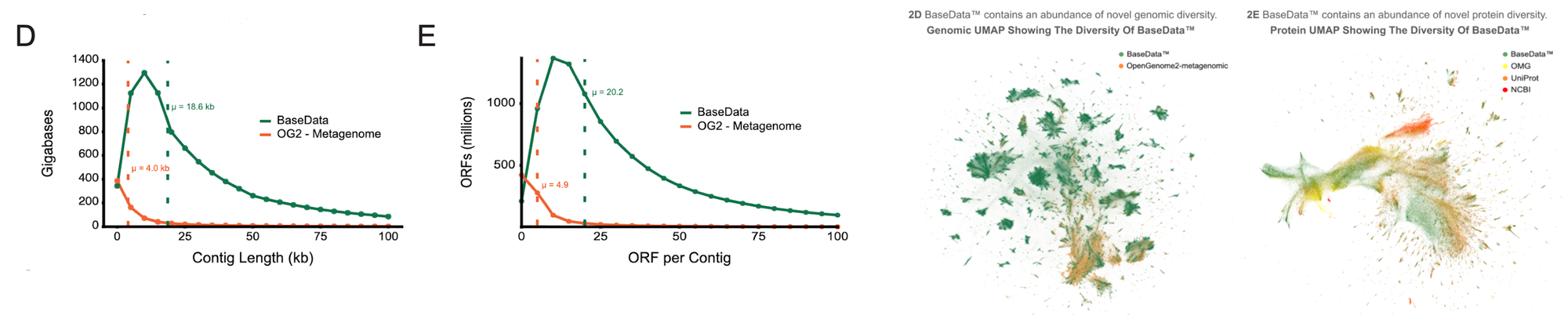

- Is what goes into the model feature complete in the sense of does your data have sufficient observability and context to answer the questions of interest? E.g. Basecamp Research attributes their improved scaling to their proprietary dataset having longer sequences will provide fuller context surrounding the genes.

- If the conditions above aren’t true, how can you create a data generation engine / supply chain?

- Does your post-training system orient the system to the right outcomes? Whereas pre-training can include bad data, post-training must steer the system to executing only the good outcomes, which requires you build the capabilities to filter out good from bad examples and fine-tune by aligning the base model with real-world data you hope to emulate.

Proper Evals: Validation Loss or Perplexity is Necessary but Insufficient

Across all fields, standard metrics like validation or perplexity loss are somewhat correlated with downstream task performance but can’t be relied upon in isolation. After model training, teams should at the very least rigorously test the various model iterations on tasks of interest. Certain architectures or other design choices may well have a lower perplexity loss and test well on a couple tasks yet perform significantly worse across the full range of desired tasks.

As teams push towards larger scales, investing some engineering effort to build more granular evaluation pipelines may be necessary. For instance, teams can:

- Frequently save checkpoints and build systems that in real-time autonomously run performance evaluation pipelines on the more crucial downstream tasks. This may flag issues that perplexity misses, allow the team to fix it, and then return to the prior checkpoint.

- Build a dashboard that separates model training loss on in-distribution and out-of-distribution data, because increasing the latter’s share can cause the loss to rise and the appearance of the model’s improvement reversing when it’s actually still improving.

- Assess needle-in-a-haystack task performance with sensitive enough evaluations.

How to Decide When to Scale or What is the Right Scale

Once a team has thought through exactly what downstream tasks are essential and how to evaluate them, then invest time playing with small scales first. The 50M parameter class models will be pathetically useless. But training them will take a couple of days and the data points from scientific experiments across different hyperparameters, architectures, etc. is worth it to assess differences in scaling trajectories.

100M to 1B parameters class models can be done within a week or two. From there, if scaling suggests performance isn’t plateauing and further improvement is required for the essential task, then go for larger models.

The right size is a function of pre-training budget, required performance on desired tasks, and downstream use cases and their inference intensity. E.g. if the model will be integrated into other platforms for regular agent inference, a 100B parameter model will be a nightmare, though you can of course distill larger models. It’s generally best to be not much bigger than the minimum size necessary for the desired downstream tasks.

Lastly, teams might want to answer specific questions like does a new datasource improve the model or simply introduce noise. Only build what’s necessary to answer that specific question, not the full complexity of a production engineering environment and all the possible datapoints.

Surrounding Infrastructure Engineering Effort

We (and sometimes our portco’s too) have been surprised by how much effort it can take to set up a system that can rapidly run all the tests above and plausibly produce robust scaling. And, as teams push beyond 10B+ parameters they get into the territory of high performance computing infrastructure and platform requirements like multi-node networking.

Depending on the complexity of the problem it can take between 6-18 months to solve the sorts problems below, each of which require substantial effort:

- Dataset processing: evaluating new datasets, adjusting batch effects, data distributional biases, tokenizing and encoding to the right dimensionality, etc.

- Necessary compute processing challenges for the domain: for those working with large data sizes, the most intensive infra effort may be a pipeline that correctly loads all of the data sets, structures them in the same format, and has the capacity to process the context size necessary to make an accurate prediction. For instance, with autonomous driving, the model makes a decision about 10 times per second. Each time the system must be fed with and process a stream of 2048 x 1280 pixel images from 11 cameras which combines in a token length of a small book while also maintaining some degree of temporal memory. It took the LLM world over four years to increase context length from 1024 to 1M. Similar engineering challenges had to be solved before AV models could process that scale of data frequently.

As an example of how complex these frontier efforts get even at reasonably small organizational scales, take this excerpt from Generalist:

Building the operations and ML infrastructure to support this is no easy feat. For robot models and data at this scale, we built custom hardware, dataloaders, and network infrastructure (including laying new dedicated Internet lines) to support the uplink bandwidth from a diverse set of data collection sites all around the world. We’ve negotiated multi-cloud contracts, built custom upload machines, scaled to O(10K) cores for continual multimodal data processing, compressed dozens of Petabytes of data, using dataloading techniques behind frontier video foundation models, capable of absorbing 6.85 years of real-world manipulation experience per day of training.

Required Culture

These efforts are highly multidisciplinary including infrastructure engineering, platform engineering, Kubernetes, traditional software development, running real-world experiments (wet-lab, robotics hardware, AVs, etc.) and integrating that experimental data.

It’s vital for the respective teams to be collaborating deeply from the start, even if each group doesn’t understand half of what’s said in the meetings. This is especially true of engineers and domain experts so engineers intimately understand how the product will actually be used and the non-obvious design specs for what exactly is needed.

Conversations could include “This is how it should be prompted. You then annotate the genes, look at the Pfam domains, use ESMFold, calculate the pLDDT using this methodology.” A lot of design choices also sit at the overlap of computational pipeline decisions and domain expertise, like context length. While that sounds like a purely computational decision, the domain expert must advise that “we need 3 contiguous gene domains to capture the proper biology.”

How Do Scaling Laws Vary Across Fields?

LLMs and image generation are the only domain where scaling has been robust enough that it has transformed their respective industries.

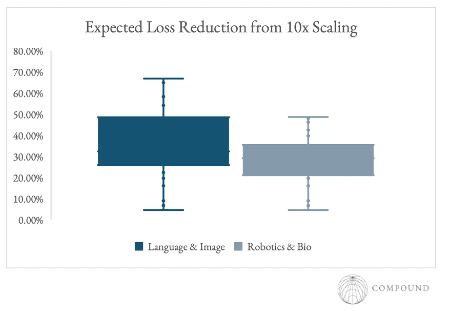

Scaling laws in those domains are more than 2x as steep as those of robotics, bio, and world modeling. Per nearly 80 scaling laws papers we collected, the expected performance boost from scaling models up by 10x in these respective domains is 32% vs 15%.

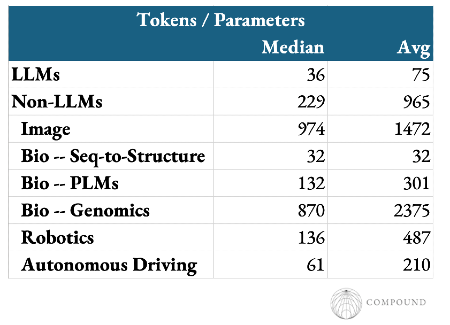

Language models also stand out as requiring far less data for a given level of parameters or compute. The Chinchilla optimal recipe suggests a compute optimal tokens:parameters ratio of ~20, though almost no large models follow that advice. Even still, they’re often a nearly an order of magnitude less data hungry than other domains’ models.

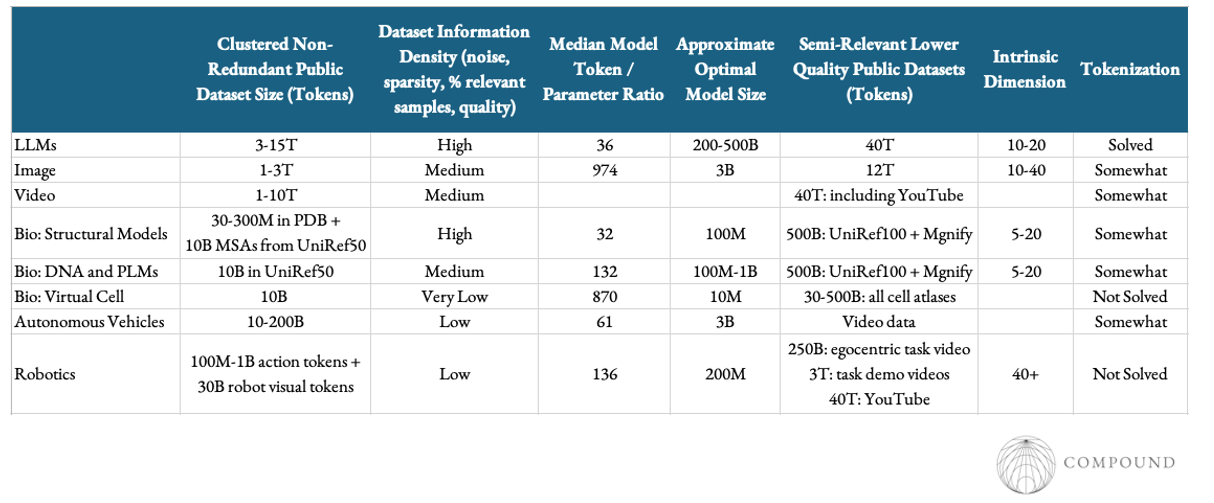

Each domain has its own wrinkles that may contribute to the above observations. But language appears unique in at least a few ways:

- Nearly infinite dataset for free: access to their entire internet allowed them to robustly scale across many OOMs, filter out low quality data without worrying about dataset size, and experiment with what kinds of data is most useful.

- Text and video are universal representations of information and task interface: most non-physical tasks we value have already been described in language, allowing for increased generalization.

- Tokenization schemes worked well from the start: no language processing algorithm has significantly beaten byte-pair encoding since its introduction in the 90s, not even clever recent methods like H-Nets. LLM researchers of course had to fiddle with the exact implementation given LLMs’ tremendous usage generality. But, no other domain has cracked even the first-order tokenization to a similar degree.

- Its intrinsic dimension is far lower than other domains: language’s ID is ~10 and LLMs’ datasets’ ID is ~15-20. The lower the ID, the faster the scaling.

- The models need relatively 5-10x less data for a fixed number of parameters / compute: While frontier labs have since augmented their initial dataset by spending $10B+ on high quality data generation, that number is relatively small considering their scale and economic impact/value.

- Off-line pre-training evaluation metrics happen to correlate quite well with downstream performance: most other fields have had more trouble coming up with a way to understand the usefulness of their models during training

All told, language and visual modalities sit in quite privileged positions as seen below. Most technical subdomains lie firmly in the data poor regimes and often have far lower information density. So, the core struggle for companies in these spaces is building a data engine that can cheaply scale.

Theories on Each Field’s Struggles and Remedies

"All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way".

Bio: Structural Models

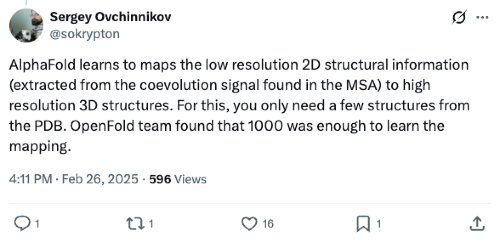

The ambient dimensionality of even short 100 amino acid proteins fills more possibilities than the number of atoms in the universe. Yet, AlphaFold navigated it with just 93M parameters.

It compressed that space so effectively that five years later there is still no family of models in AI for science that has been more successful. Its technical triumph is broadly attributed to the fact that it, like LLMs, was birthed with the gift of an outstanding dataset for free in the PDB with its 200K nearly atomically precise structures.

However, I’d argue that equally important is that the data is constrained to a highly structured and very low-dimensional manifold.

Physics dictates this astounding dimensionality reduction. A protein chain with L residues theoretically has 2L degrees of freedom (phi/psi angles). However, steric clashes, hydrogen bonding requirements, and the hydrophobic effect constrain the viable conformational space to a vanishingly thin manifold. Evolution constrains it even further, as mutations must preserve the stability of the fold.

The result is a few striking observations:

- The frequency of protein folds follows a power law where a few types like TIM barrels appear across thousands.

- Structure space is shockingly compressible at a tertiary resolution. A study estimated that ~600 tertiary motifs can describe >50% of the known protein structural universe at sub-Å resolution.

- The ID of protein family sequence space is estimated to be 6-12, meaning evolution effectively explores only ~6–12 independent directions per family (and this range is similar across many families). ID across all proteins appears not much larger.

- OpenFold demonstrated that training on a clustered subset of just 10K diverse chains yields accuracy comparable to training on the full PDB, implying that the "effective" size of the structural universe is small. And, ~90% of its final accuracy was achieved in just the first ~3% of training compute time.

This low ID explains the "saturation" behavior observed in protein models. Once a model has sufficient capacity to represent these ~12 degrees of freedom and memorize the ~1,000–10,000 unique fold families (the "quanta" of structure), adding more parameters yields marginal gains.

Practical considerations constrain the space further and bias the data towards useful proteins:

If you want to structurally characterize a protein, you first need to express the protein. The expressed protein (and any binding partner) needs to be decently stable to withstand purification, freezing, and whatever else you do to it. To resolve a high quality structure, you also need the protein to not aggregate too much. And of course, you need to convince someone to give you money to run this experiment and care enough to run it. So the protein is likely “important” in some way.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the problem statement that AlphaFold had to solve was a small subset of the full problem as articulated below. That subproblem happens to be quite useful.

All told, the field boasts an exceptionally constrained problem with a high quality, information dense dataset (that also happens to be biased towards developable drug-like molecules). Hence, AlphaFold and AlphaFold3 remain the top AI for science models despite only having 93M and 368M parameters, respectively.

Moving forward, teams will be competing for generality as it’s still not obvious that the current models do that much more than memorize evolutionary patterns. As such, models still struggle to go beyond stitching together non-ambiguous regions without evolutionary information, most hard commercially relevant targets, intrinsically disordered proteins, cryptic pockets, etc.

To get there, one relatively simple algorithmic fix is to more deeply implement search into these models as discussed by Sergey in this podcast. Others include expanding beyond the PDB to generate large-scale experimental data and incorporating physics with hybrid NNP models like Compound portfolio company Achira is pushing towards.

Isomorphic’s IsoDDE achieved a step function leap in generality and addressed the aforementioned problems like cryptic pockets. But we’ve seen little indication that they’ve materially ramped wet-lab experimentation and have heard from teams that they’re stingy with data generation contracts.

Maybe Demis was right when he challenged teams in the space to stop complaining about a lack of data and instead create more innovative algorithms.

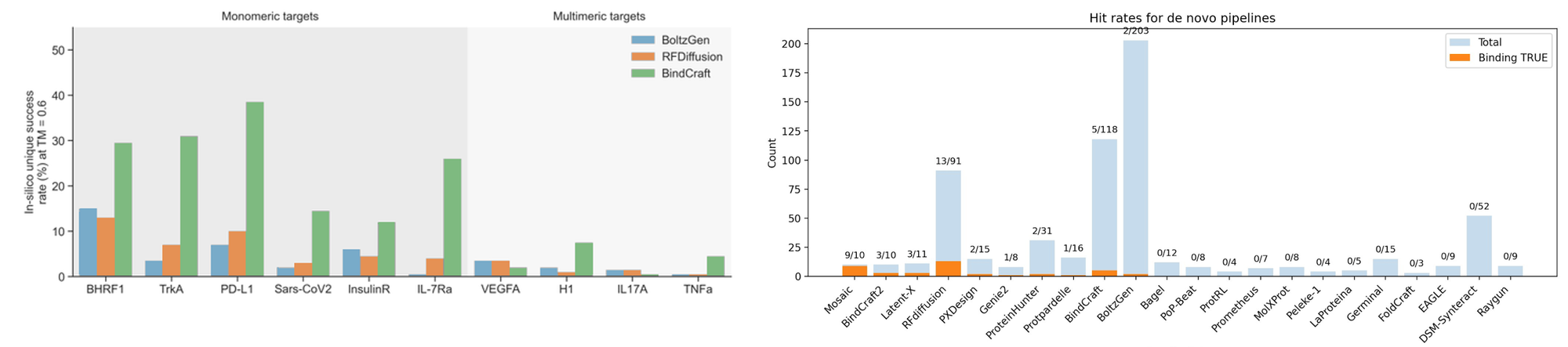

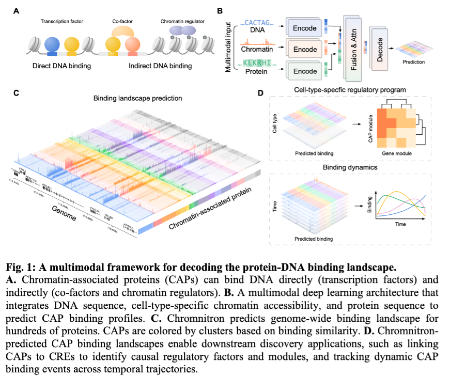

Bio: DNA and Protein Language Models

At first glance, publicly available sequence datasets appear similarly large. Indeed, the SRA is home to over 36 petabytes of sequences!

To match the dataset, several teams scaled up to huge sizes. The hope with scaling these models is that they'll progress from learning simple signals like conservation to picking up sparser, more complex patterns like coevolution and contacts and maybe eventually develop emergent capabilities like learning the underlying physics of protein structure

However, some 15-100B parameter models have been bested by 30-100M parameter models. What gives?

- Datasets’ lack of diversity drastically overstates actual size: the UniRef50 version of UniProt clustered at 50% non-redundancy contains less than 70M sequences, or 99.999% smaller than the raw sequence content of the SRA.

- Annotation depth is limited: <1% of UniProtKB entries are manually curated

- Missing context: most sequences lack functional or taxonomic assignment

- Short fragments dominate: little structural or contextual signal for machine learning

- Noisy data to begin with: consistent data collection and processing are non-trivial

For these reasons, scaling models beyond the compute optimal size implied by the UniRef50 dataset has yielded no improvements.

Basecamp Research sought to fix this by building a highly differentiated data supply chain that encourages diversity and collects higher quality samples with consistency and proper metadata context. Their dataset is 10x the size of those publicly available after adjusting for diversity.

Their model performs SotA on downstream tasks. Interestingly both their results and those of ProGen3 report a significant share of the gains to scaling appear to be more so around diversity of samples generated.

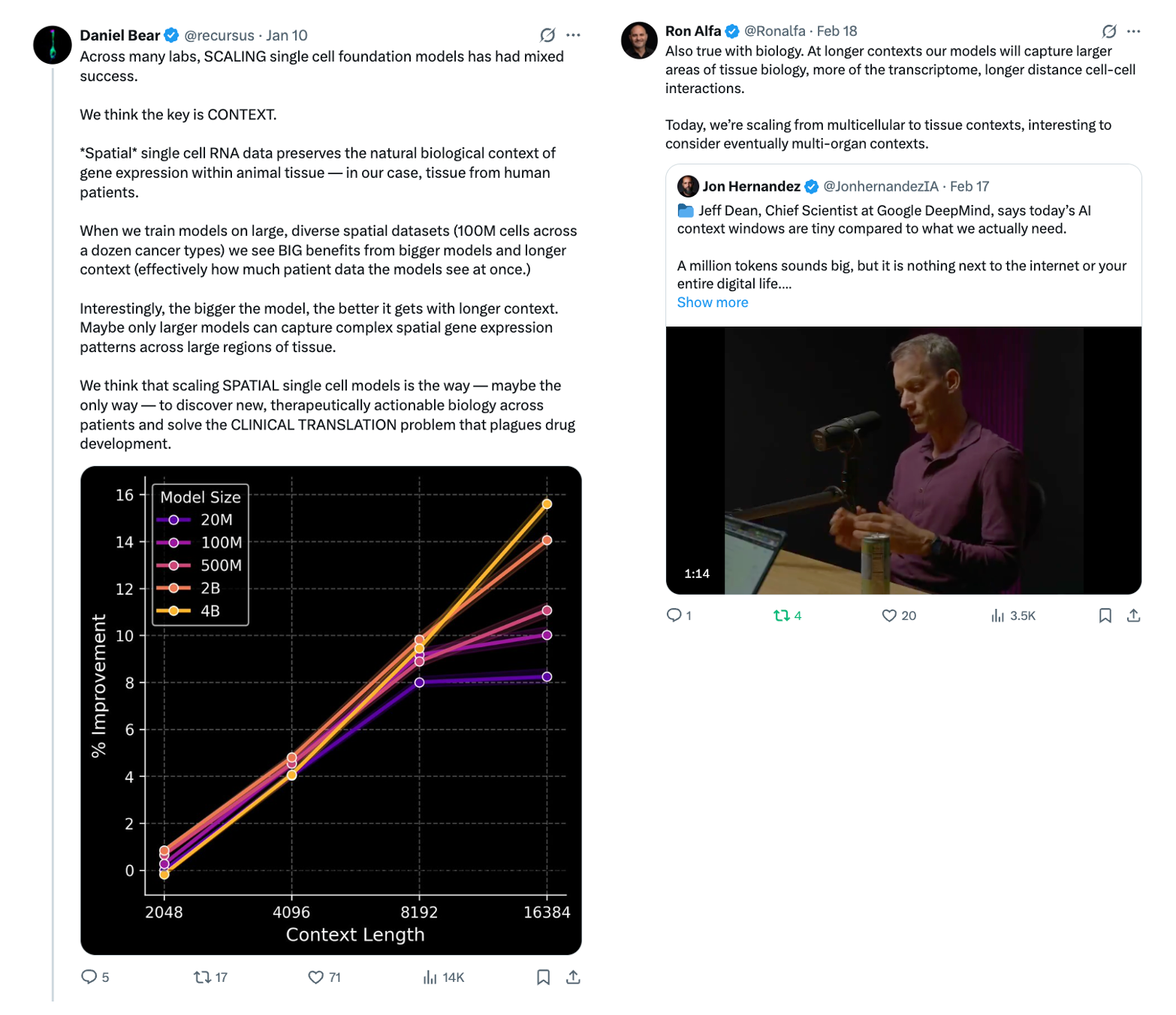

Bio: Virtual Cell Models

Despite some models being scaled up to billions of parameters, almost no model has beaten basic statistical methods like linear models.

- The data generation process has tons of artifacts because of the damage of going from tissue to dissociated cell, chewing up the extracellular matrix, putting the cell in a centrifuge, and lysing them – all of which takes at least an hour during which environmental factors further alter the cell. This along with batch effects and hardware error means that the inherent noise of the datasets can be 3-30%.

- Current technology only sequences at a depth of 10-20k UMI and dissociated single-cell RNA data possibly isn’t all that interesting for downstream applications as it misses the important variance a large model could capture

- Adding further sequencing depth, context or modalities is expensive

- For the data that is captured, it data has extreme sparsity with often over 90% of the entries in the 20k x 20k matrix filled with zeros and perturbations only causing changes in a few gene expressions, making the modeling itself non-trivial

- The data might be quite high dimension at 10-70, though that’s not well established

- Outcome metrics and benchmarks aren’t thoughtful

In-Context Tissue

Noetik believes that the spatial context from spatial transcriptomics from tissues collected directly from real patients is essential for answering questions relevant to drug discovery, allows their models to exhibit more robust scaling, and won’t require an unwieldy data generation effort to generalize sufficiently.

Multimodality

AlphaGenome beats the basic baselines by using a U-Net inspired architecture to unify 11 modalities and to process both 1D and 2D interactions, and 1Mb inputted sequence context with base-pair resolution.

Encoding thoughtful inductive biases

GPN-Star, the other model to beat basic baselines, expands on GPN's whole genome alignment with explicit phylogeny, first doing in-species self-attention then cross species cross-attention via pairwise distance from species trees.

The next step is to unify both the complementary signals of conservation/evolution via MSA and functional genomics.

Decreasing Costs to Scaling

Cellular Intelligence built hardware that orchestrates sequentially segregated capsules to run massively parallel cell-signaling perturbation experiments across up to 27K unique combinations in a single run. Meanwhile Arc devised a method that cuts costs to run a perturb-seq screen by 4x and increases gene detection per cell by 50%.

Explicitly Embedding Time into Training

Properly modeling how cells work will require incorporating their dynamics over time, both internally and in populations. Currently, no technology exists to perturb cells and measure dynamic live responses in high throughput, though some tools are emerging. Two recent models push towards incorporating dynamics.

Robotics

How quickly robotics' scaling laws take shape is a near-existential question for the cornucopia of generalist robotics startups. The rate at which these systems can not only learn but truly master new skills and environments will govern the pace at which they secure contracts across diverse commercial deployments (the purpose of generality) which in turn determines the scale and diversity of their training data, which drives performance, and so the flywheel spins.

All the while, they're racing against purpose-built systems perfectly content to collect data for a single task. And, a bitter lesson of robotics is resurfacing once more: the unreasonable effectiveness of on-embodiment data captured in the field doing the actual task remains stubbornly hard to shortcut.

Yet, robust scaling laws in robotics have only very recently been hinted at despite decades of work on robotics for a few core reasons.

- Robotics is likely the most high dimensional of all these domains as it’s the joint modeling of video + language + actions + the robot’s degrees of freedom. A conservative estimate of its ID would be 40.

- Equally important, there are currently no reliable offline metrics that serve as a good proxy for on-robot performance. Moreover, sequential decision-making introduces compounding errors, which means the evals need to capture how mistakes accumulate across steps. That requires generating the states that would result from each proposed action which is effectively a realistic simulator.

- The lack of offline metrics also means nobody knows what is useful data or how to test that before using it to train a model. Indeed, the “Scale AI for robotics” plays can’t simply collect and sell data; they must go all the way to training models themselves to show that the data is useful. The things that do seem clear about data is that quality and diversity matters significantly more than sheer volume 1,2,3,4,5,6. Yet, existing robotics datasets are almost exclusively pick and place tasks. Eric Jang relates this observation to the Quanta Hypothesis of neural scaling introduced at this post’s outset and stipulates that this lack of diversity in tasks or “quanta” in robotics datasets may help explain the lack of robust scaling:

“Even though we may collect enormous numbers of demonstrations & hours of data, the data do not contain enough diversity or "underlying subtask quanta" for the losses to "meld together" to form a clean scaling law.

It remains a mystery why natural data, sorted by subtask difficulty, seems to form a Zipfian distribution. Are tasks we perceive as "difficult" actually nothing more than "infrequent" in our training distribution? There is relationship between the length of the shortest program that can generate some data, and the frequency of that data. If a subtask were *more* frequent, then you could actually shorten the program needed to generate it, thereby making the task easier from a Kolmogorov Complexity POV.

And if you assume my previous claim about robotic scaling laws is true, why makes robotics data have such bad zipfian coefficients? Does the coefficient only get "good" once you do the tokenizer + dedup + operationalize the data collection just right?

Does a hard subtask take more steps to learn because it requires representations from "easier" subtasks to be learned first? Representational dependency enforces a strict ordering in tasks that can be learned (task B cannot be learned until task A is mostly learned, task C cannot learn until B is mostly learned)? This could explain why there is an "ordering" of difficulty - it arises from natural ordering of dependencies in distributed representations like DNNs.”

- Lastly from a data perspective, robotics is lucky to have access to all text and video on the internet. However, these datasets’ distribution is not that well aligned with downstream robotics tasks and isn’t in terms of robotic action controls. Getting the pre-training recipe right to utilize this resource has been the focus of the last few years.

VLAs: The First Pre-training Paradigm

The first major attempt to utilize the internet’s data for pre-training came with VLAs three years back. We wrote a few years back about VCs pattern matching RT-1 to robotics’ “GPT-1 moment” and YOLO’ing money hand over fist. Since then, over $6B has been invested in generalist robotics startups at a combined $70B+ market capitalization, three years have passed and we’re now starting to see the first glimmers of scaling in robotics.

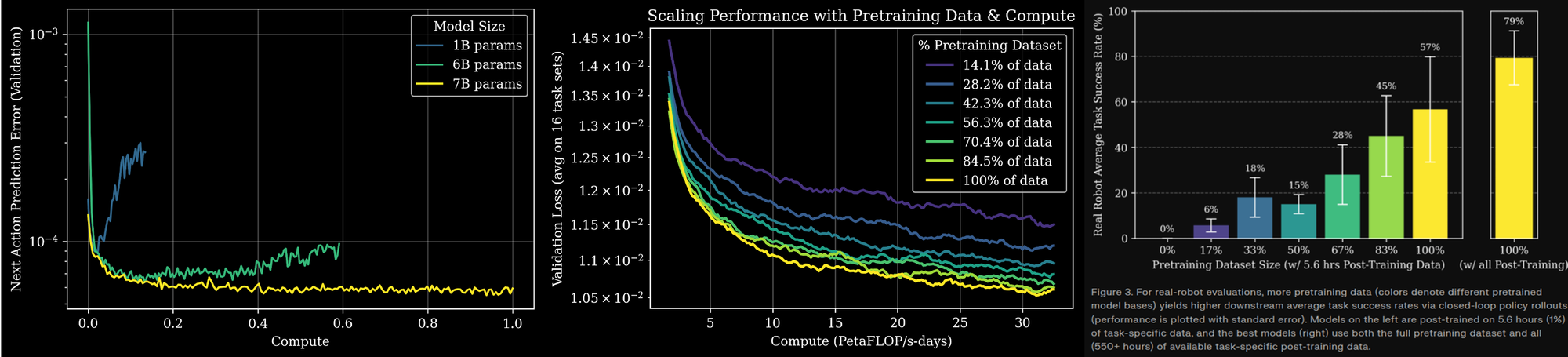

Late last year, Generalist reported the first clear evidence of scaling laws within robotics and that for the first time practically any relevant data will make the system better at each individual task. They pre-trained a VLA on their large real-world dataset generated with their UMI gripper using next action validation loss and showed that scaling pre-training reliably benefited downstream task performance.

A striking but speculative byproduct of their experiments is the suggestion that models have to be fairly large to effectively absorb vast physical interaction data. Models smaller than ~7B parameters exhibited something similar to ossification under data overload, which has been observed on small LLMs of 10M parameters, not 1B. Time will tell if this early result that echoes Moravec’s Paradox will hold broadly and that there will be a relatively high minimum threshold of model size. A high model size floor would further stress edge compute’s limited capacity, which has already pushed teams away from a monolithic model to System 1 & 2 and now even to Systems 0, 1 & 2 model hierarchies.

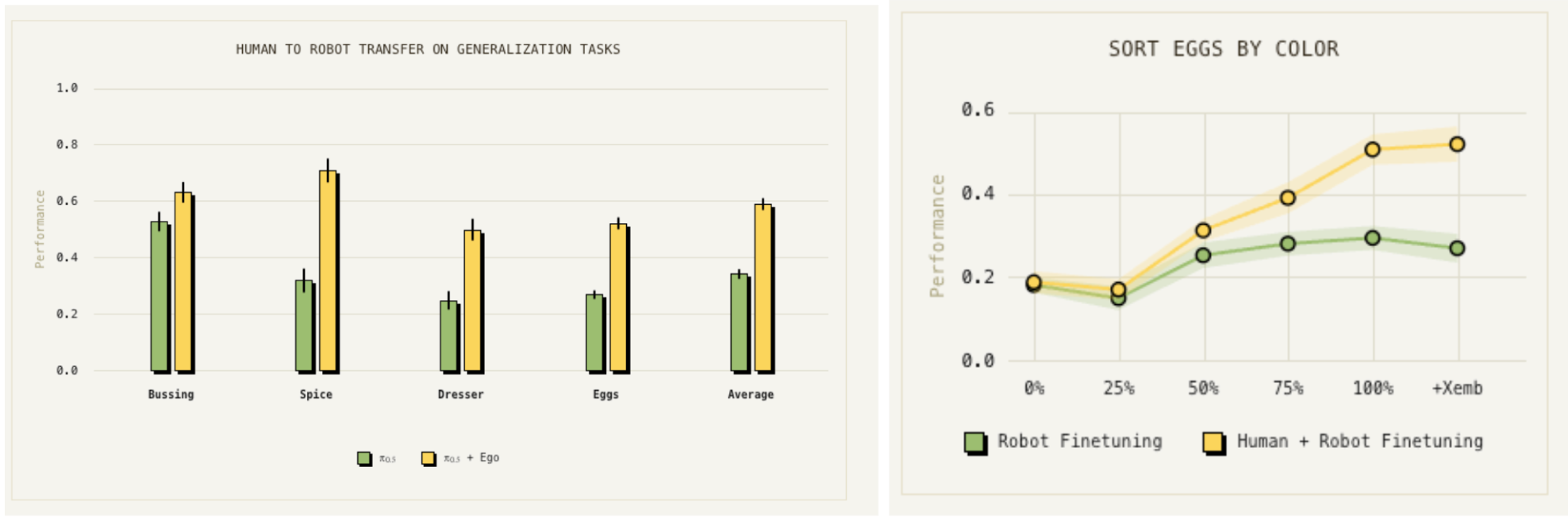

Meanwhile, Physical Intelligence showed the first glimpse of an emergent behavior from scaling. They fine-tuned their base VLA on human egocentric data and were surprised to find that it improved generalization on tasks not seen in the robotics pre-training data by as much as 2x. Upon examination, they found that models with small scale or no pre-training represented data from robots and humans with very different features whereas larger models aligned more closely similar demonstrations regardless of embodiment. This result shows that just as with LLMs, scaling robotics pre-training effectively should allow teams to utilize ever more types of data and crucially cheaper and more abundant data sources.

While VLM-based VLAs remain the most popular architecture amongst the various SotA training methods, we believe they aren’t the end all be all. As top researchers have pointed out, they’re more like a language-vision model with action grafted on at the end, don’t natively model cause-and-effect in the physical world, and thus regressing to actions is like sucking supervision bits through a straw.

For these reasons, VLAs excel at semantic generalization but struggle to generalize to unseen physical motions in novel environments.

The training paradigms we at Compound are particularly excited about and believe will yield the most robust scaling are world modeling and RL directly from robot rollouts.

World Modeling

Compound portfolio companies Wayve and Runway have pioneered world modeling within autonomous driving and Hollywood-worthy video generation, respectively. Beyond those two companies we at Compound have been writing about and investing in simulation since 2010s.

Wayve in particular has been working on training within simulation for 3+ years now and scaled their GAIA world model up to 15B parameters. Scaling laws in autonomous driving (in terms of driving quality) depend largely on the number of diverse examples of closed-loop interventions where the deployed model fails and is corrected. The only cheap way to get that data is to generate it within simulation.

But their experience reveals the difficulty of getting both realism and diversity in simulation right. A world model trained on good driving data will literally generate video of the road widening to avoid simulating a crash it's never seen. A tractable near-term approach is rolling out small synthetic counterfactuals from real data, filtering aggressively, and feeding useful samples back into training.

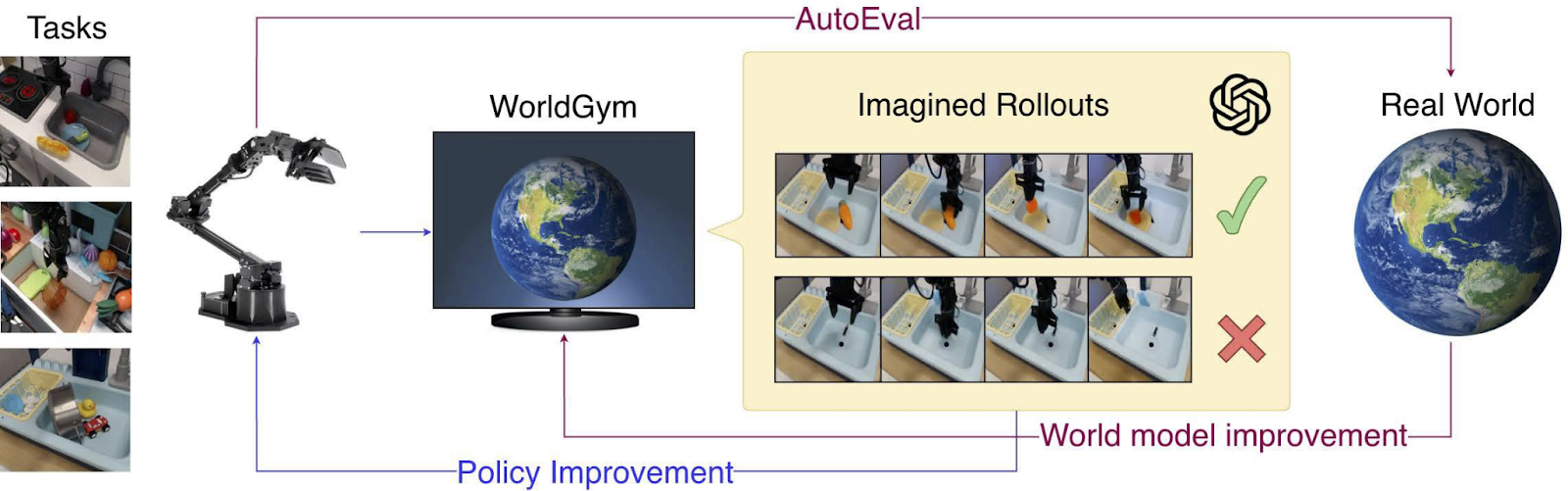

Within robotic manipulation, Nvidia’s DreamZero is a 14B autoregressive video diffusion model that jointly predicts future video frames and actions in a single forward pass. This enabled generalization that pure action prediction can’t. It beat the best VLA baseline by 2x on zero-shot task progress and achieved the most efficient embodiment transfer to date.

DreamZero attempted correct motions for entirely novel tasks like untying shoelaces, drawing on physical knowledge from its video backbone. Whereas, on unseen tasks, VLAs defaulted to pick-and-place motions regardless of the instruction, suggesting overfitting to common action behaviors rather than learning task semantics.

1x extended the video pre-training training pipeline by adding mid-training on egocentric human video and fine-tuning on their robot’s data. They also showed that video generation quality and captioning correlate with downstream task success, suggesting that improved underlying video modeling and generating multiple rollouts to select the best are easy waves to ride.

Other exciting work include DeepMind using world models to accurately evaluate generalist policies, using RL within a world model to fine-tune a policy and trying test-time training on novel scenes; a chain-of-thought method for generative video reasoning which could be extended by doing the reasoning entirely within visual-physical simulation without any language scaffold; and Nvidia’s Cosmos Policy which has no inverse dynamics model, no action head, and only the single video world model.

Together, these works spell out how this future may unfold:

- Scaling & improving the underlying video model

- Devising ways to increase its outputted diversity and long-horizon generation

- Running test-time inference to improve pre-training datasets like Wayve and 1x

- Reasoning within video itself not language

- Test-time inference to simulate and reason about novel actions, environments, and objects

- Still yet to be explored are things like weaving proprioception and tactile sensing into training, alternative latent spaces to pixels

Autonomous reinforcement learning directly from robot rollout

An exciting alternative approach that doesn’t depend on the rapid scaling of egocentric datasets involves taking that video pretrained model and then doing AlphaZero-like learning from real-world unsupervised environmental experience. This requires not just excellence and creativity in model training but also a devotion to making exceptionally cheap and manufacturable but reasonably durable robots.

Pantograph is embracing this vision by building thousands of ~1ft tall wheeled robots that look crab-adjacent. They’re able to handle 1kg continuous payload and the critical components have been put through 10k+ hours of stress and endurance testing.

Our robots learn by doing: touching everything, tossing things around, finding the exact balancing point of two wooden blocks. Thousands of robots, millions of hours of data. pic.twitter.com/QbkT3zng5A

— Pantograph (@pantographPBC) December 23, 2025

Their initial data collection phase will focus on what internet video misses: texture, pliability, etc.:

This first phase of data collection will look something like a robot preschool: thousands of small, inexpensive robots, touching everything they can get their hands on, tossing things around, finding the exact balancing point of two wooden blocks, bending, rubbing, scraping, building up a model of the world around them. This data will be the foundation upon which we will train increasingly capable models.

Other teams we admire pursuing cheap real-world data generation include Aloha-style low-cost arms, and UMI platforms like Sunday and Generalist.

The Bottom Line

Across all these fields, a strategic fork is emerging: companies building narrow AI products around a precisely specified problem or horizontal foundation models geared towards generalization.

Both teams must hold opinionated views on exactly what data to scale, how to build evals that correlate with commercial outcomes, what the precise specification of the technical problem they're solving actually is, commercial product’s use, etc.

But the difference in demands upon the respective organization types couldn’t be bigger.

The narrow-AI path using AI to build a specific product faster favors deep domain expertise tightly integrated with a precisely specified problem.

Whereas the foundation model path demands truly world-class talent across multiple disciplines and a highly differentiated data engine that scalable produces relevant data.

Perhaps it's time for bio and robotics founders to start recruiting at Jane Street. Or perhaps this talent bottleneck loosens when frontier LLMs begin to automate ML research itself, and then the ability to run ML experiments in parallel at scale could quietly become one of the most important edges in AI for science.

Data engines can take one of two forms. The first is a technical innovation that makes collection dramatically cheaper or more diverse (e.g. Pantograph, world models, UMI, Cellular Intelligence’s parallelized assay machine). The second is business model innovation where revenue directly subsidizes data generation (e.g. bio banks like Tempus get paid for the very data that trains its models while Basecamp Research's royalty system incentivizes biodiversity sampling worldwide). In both cases, the flywheel compounds.